[Dec] Rising status of Korean picture books on international stage

Date Nov 29, 2021

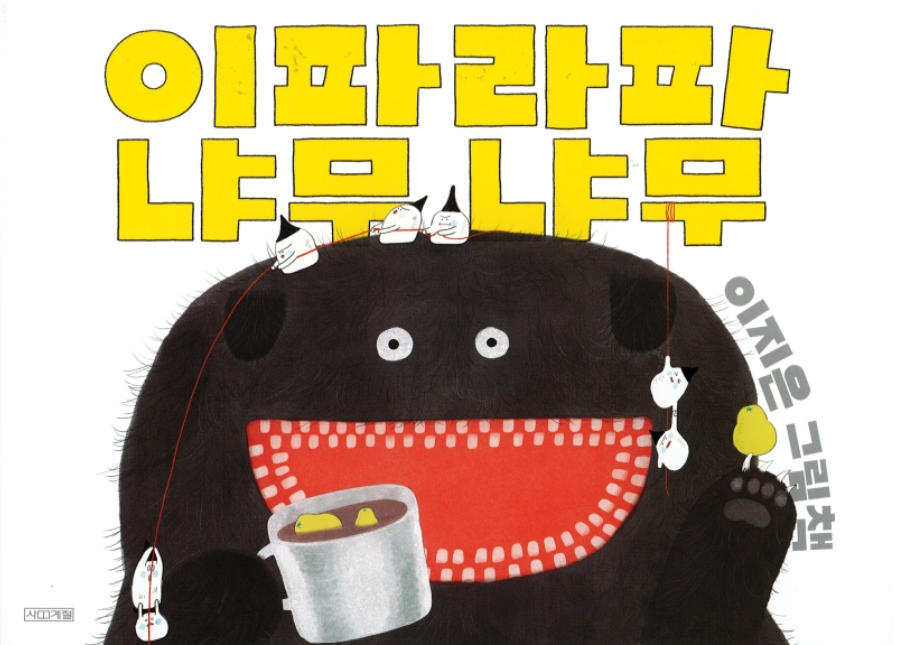

The cover of the picture book, "Iparapa Yamooyamoo," by Lee Gee-eun, which was named the winner of Bologna Ragazzi’s Comics/Early Reader category this year. Courtesy of Sakyejul Publishing

The cover of the picture book, "Iparapa Yamooyamoo," by Lee Gee-eun, which was named the winner of Bologna Ragazzi’s Comics/Early Reader category this year. Courtesy of Sakyejul Publishing

●Due to its turbulent modern history, Korea is a late bloomer when it comes to the rise of quality picture books.

●Critics say Korean picture books have been winning global literary prizes because more writers have been experimenting with new forms of creativity.

Despite its short history, the children’s book industry in Korea has shown remarkable progress in just a few decades, with the number of authors and works gaining international recognition continuing to grow.

A notable moment in the industry’s history was the establishment of the Korean Children’s Book Association (KCBA) in 1980 that aimed to introduce and popularize children’s literature written and illustrated by Korean authors – a genre that has long remained marginalized.

A decade later in 1990, “Chobang,” the first bookstore in the country dedicated to children’s books, opened in Seoul’s Seodaemun-gu District. The children’s book publishing industry began to expand quickly here during this period of rapid economic development and a wave of cultural globalization.

In 1995, the Korean Board on Books for Young People (KBBY), a branch of the renowned International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), was established to promote local works on the international stage.

“While picture books in other countries [especially in the West] saw their heydays from the turn of the 20th century, it was a different story for Korea – a country that underwent the 1910-45 Japanese colonization, followed by the 1950-53 Korean War,” replied KBBY President Shim Hyang-boon in an e-mail interview with Korea Here & Now.

“For a long time, the country wasn’t in a position to promote children books that reflect its visual culture internationally… But starting in the 2000s, more Korean publications began drawing attention and expanding their presence overseas.”

The remarkable growth of Korean picture books on the global stage has been observed in the most recent Bologna Ragazzi Award – annual literary prizes presented at Italy’s Bologna Children’s Book Fair since 1963. The Bologna Ragazzi is one of the most prestigious awards in the world of children’s book publishing, along with the Biennial of Illustration Bratislava (BIB) and the Hans Christian Andersen Award.

The first Korean books to win recognition in Bologna were “Metro Arriving” (by Shin Dong-jun) and “Red Bean Soup and Tiger” (by Cho Ho-sang and Yun Mi-suk) in 2004. Since then, almost every year, Korean illustrated books have won a Bologna Ragazzi Award or an honorable mention. Most recently, last June, Lee Gee-eun’s “Iparapa Yamooyamoo” was named the winner of Ragazzi’s Comics/Early Reader category.

Besides being awarded for their individual publications, some picture book authors in Korea have been recognized for their lifelong contribution to literature for children and young adults.

In 2016, Lee Su-zy became the first Korean artist to be shortlisted for the Hans Christian Andersen Award, also referred to as the “Little Nobel Prize.” IBBY has awarded it to children’s book authors and illustrators every other year since 1956 and 1966, respectively.

And last year, another writer, Baek Hee-na, was presented the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, thus becoming the first Korean writer to win that international prize for children’s literature. The Swedish Arts Council started awarding the eponymous prize in 2002 to celebrate the author’s life.

“Baek Hee-na is an artist who is renewing the picture book medium through the bold and uncompromising development of new techniques and artistic solutions that inject elements from handcraft and animation into her books in new and exciting ways,” the prize jury members Elina Druker and Maria Lassén-Seger wrote.

Critics attribute the rising status of Korean children’s books in recent years to the remarkable growth in the quality and variety of the illustrations as writers are given more freedom to experiment with different forms and aesthetics.

“We are starting to see more writers, as well as readers, who view picture books not simply as a commercial product, but rather as an artwork that one can experiment with,” said Choi Hye-jin, author and vice president of the Picturebook Association. “This is a divergence from the early 2000s, when there was much higher demand among readers for commercially published collections of ‘educational cartoons.’”

KCBA’s picture book selection committee member Kim Hyun-jung echoed those sentiments: “Nowadays, we see so many more illustrations speaking with vibrant visual languages of lines and colors that make them comparable to pieces of art. Although Korea is decades late compared to the United States and Europe in terms of its recognition of picture books, the artistic merits of our authors are definitely gaining ground on the international stage.”

She added that in addition to the efforts made by the writers themselves, the publishers and institutions who have invested in promoting, exporting and translating these books for the overseas market have played a significant role in the growth of illustrated books in Korea.

**If you have any questions about this article, feel free to contact us at kocis@korea.kr.**

The Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism's "Korea Here & Now" work can be used under the condition of "Public Nuri Type 1 (Source Indication)."